Some of the most memorable adventures start with a simple, mad idea. This was one of them.

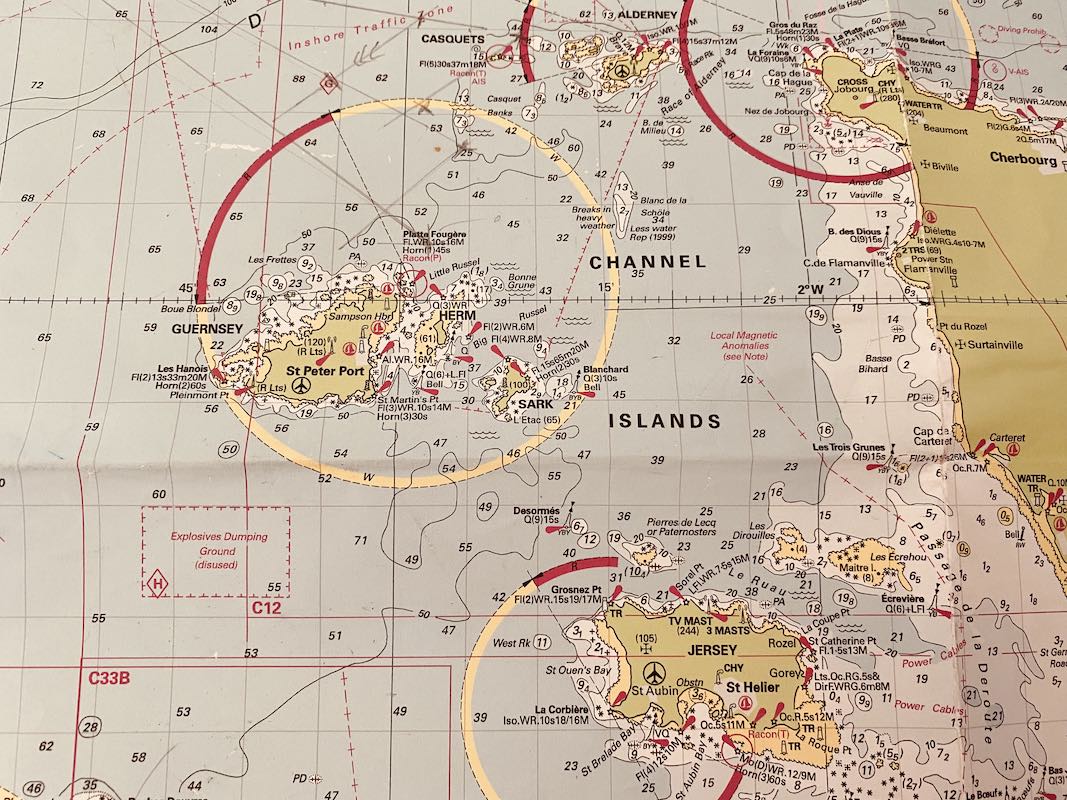

When you glance at a nautical chart of the English Channel, certain landmarks stand out. The chalky trapezium of the Isle of White at almost dead centre. The huge promontory of Cap de la Hague that marks the northern tip of Normandy, sticking up into the Channel like a proverbial French finger brandished against the marauding English. And the other defining headlands of Beachy Head, Portland Bill, Start Point, and The Lizard, the sea-marks of times past and to come. But something else on this chart – something small but deeply intriguing – pulls the mariner’s eye south from those prominent features and towards the Channel Islands.

Almost at the centre of the archipelago lies the tiny island of Sark; a strange, beautiful, star-shaped dot on the chart. It’s arguably the most interesting feature of the Channel Islands as a whole. It comes complete with dramatic cliffs, caves, isolated coves, a tiny but permanent local community, tractors instead of cars for transport, no income tax, and a method of self-government that only parted with the feudal system in 2008 (yes, really). Sark lies just over six nautical miles (13km) east of Guernsey and just over eleven nautical miles (21km) north north-east of Jersey.

In this article

Touring & Exploring

Adventure & Lifestyle

Travel & Inspiration

For sailors and paddlers, one of the most compelling and also complicating aspects of getting there is the extremely strong tidal current that flows through the channel of the Grand Russel, separating Sark from the smaller islands of Herm and Jethou, and through the narrower channel of the Little Russel, that separates those islands from Guernsey itself. On spring tides, the tidal streams in both the Grand Russel and Little Russel exceed five knots, and around the headlands and various offshore rocks the stream can be as strong as seven knots (and in certain places even more than that): that’s the speed of a large river in spate. This makes the crossing to Sark an interesting challenge, to say the least.

It has been done numerous times by experienced sea kayakers, and in good conditions it’s an excellent trip by kayak. I could find no evidence of the voyage having been done by anyone on a standup paddleboard, which is of course not to say it hadn’t previously been done, or would not be possible. A strong paddler in a high performance sea kayak can easily maintain an average speed of six knots in good conditions. Even the fittest standup paddler can’t match that. In my experience, working with an average speed of just over three knots (6-7 kmph) is a good rule of thumb when planning long distance SUP trips in the open ocean, based on using a race board or a fast touring board.

The paddling technique and overall strategy required for a trip like this is known as ‘ferry gliding’, which as it suggests involves making an adjusted course across a strong current in order to arrive (hopefully) at the correct point on the other side. The longer the glide, and the smaller the landing point, the more complicated it is to get it right. Sark is a small island, and it takes almost three hours to paddle there from Guernsey. Since you’re transiting across water that’s moving faster sideways than you can paddle forwards, you’re essentially trying to hit a moving target. Even in very good conditions, it probably wouldn’t be easy.

Derek Hainon, the author of the excellent sea kayaking guidebook to the Channel Islands, came up with a useful way of thinking about offshore crossings in the archipelago. He describes the islands as “rocks in a river”. This particular river in question changes direction four times a day, with the six hour North Atlantic tidal cycle. The other thing is that the “river” between Guernsey and Sark, if you think of it like this, is slightly wider than the mouth of the Amazon – the world’s largest river – at Macapá, Brazil, just before it flows out into the Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, numerous tide races with large overfalls, eddies, and standing waves form in multiple locations around and between the islands. Here were all the ingredients, it seemed, for either a truly memorable trip or an elephantine epic.

The necessary weather window opened in the middle of June. After carefully cross referencing tide times, swell charts, and the wind forecast, my partner Dorka and I decided the Sark paddle was worth a shot. She’s one of the few people I know who is a strong enough standup paddler to do something like this. She’s also one of the only people I know who is mad enough to even contemplate doing so.

The Channel was as calm as a mountain lake as we left Portsmouth on the ferry; these were ideal conditions for what we had in mind. A few hours later, as we approached Alderney, the most northerly and outlying of the Channel Islands, massive swirls and interconnected eddies began to appear in the sea as we entered the Raz Blanchard, or the Alderney Race. The whole thing was on an impossibly large scale: the tide race extended around us for dozens of square miles. The Raz Blanchard forms in the channel between Alderney and the tip of Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula, and the tide stream can reach twelve knots (22 kmph) through here at certain times of the year. The French coast was around thirteen nautical miles south, Alderney was eight nautical miles west, yet even way out here the tide was rolling along like a freight train. On this particular afternoon there was almost no wind, yet still the sea was alive with tidal energy in a way I had not previously seen anywhere else, not even on my extended paddleboard expedition around Southwest England.

There are few places on Earth where the power of the moon’s gravitational effect on the ocean is as evident as in the sea lanes of the Channel Islands. There are a few places with a bigger tidal range, like Canada’s Bay of Fundy and in the Bristol Channel. But those are inshore waters, not the open ocean. To experience this kind of tidal power in an offshore, deep water, oceanic environment you have to come to the Channel Islands, and in particular to exactly where we would be heading tomorrow.

The voyage out

The sea is a canvas of deep blue, unbroken by whitecaps, as we make the last preparations and checks on the tiny beach just north of Bordeaux Quay. There’s a faint breath of wind from the northeast, but nothing of note; the forecast says it’ll drop back to less than four knots after three o’clock, when we’ll be in the heart of the Grand Russel. Let’s hope it’s right. The islands of Herm and Jethou define the eastern horizon, with the southern tip of Sark just visible to the south. Through the anticyclonic haze of high noon, it looks really quite far away. We go through the final, routine safety checks: VHF radio, check. Flares, check. Tow lines, check. Rafting cords, check. Fin bolts, check. It seems surreal that we are actually about to launch on this preposterous mission, but the weather and sea conditions are as good as they get, and here we are.

We push the boards off the shingle stern-first, spin around, and head straight out into the main channel of the Little Russel. The south-flowing tide stream has only just started, and we instantly pick it up as we contour a big rock that lies a hundred metres offshore. The Little Russel is full of rocks, some small, and some almost tiny islands, and they make useful reference points for our drift. We keep the dominant landmark of the Bréhon Tower – an early nineteenth century fort that was repurposed by the Nazis as a gun emplacement during the wartime occupation of the Channel Islands – well to our south. We make good progress across the central section of the Little Russel, wisely avoiding the sailing time of the Condor fast ferry that accelerates to 35 knots hereabouts as it heads north. The white sand dunes and dark green swatches of marram grass that define the northern point of Herm resolve into view, and soon we’re gliding through aquamarine and turquoise water as the light refracts off the sandy bottom. It’s much more reminiscent of the Caribbean than Britain. A solitary puffin lands on the water just to starboard, confirming we’re in temperate rather than tropical waters after all.

We set foot very briefly on Herm as we portage the boards across a narrow sand bar to avoid paddling around the large reef that extends seaward from the northern tip of the island. A great sluice of dark blue water now rushes in to meet us: the south flowing tide stream on the east side of Herm is now running at full bore. The dramatic, dark red cliffs of Sark’s west coast now shimmer on the horizon. We waste no time here, as we want to have time for a break on Sark to wait for slack water for the return crossing. After a very quick break to hydrate an inhale an energy bar, we push out into the stream of the Grand Russel.

Heading away from Herm and an assembled flotilla of yachts and powerboats basking in the sun and shelter of the northeast side, we create an invisible marker point around ten degrees north of the northern tip of Sark, and use that as our sighting line for the tidal vector we want to take across this six kilometre-wide channel through which the water constantly surges. The tide is now flowing faster southwest than we can paddle east, so we need to make for a point that’s at least forty-five degrees upstream of our intended landing point on Sark’s Grande Grève beach if we are to stand a chance of actually arriving there.

A large rock known as the ‘Noir Pute’ commands the lonely seascape on the northern approaches to the Grand Russel. We keep it to our port side as we make our course out into the heart of the channel. From here, with our corrected course to the north, the tide will [read: might] pull us down on to the coast of Brecqhou, a small island that lies just off the west coast of Sark, from where we can nip around into the bay where we intend to land. It sort of works, but as with so many things at sea, it doesn’t go exactly to plan.

As we approach Brecqhou, the mock-medieval castle prominent on its seaward coast provides a valuable reference point. We’re closing in, but we’re still around half a nautical mile (circa 1km) offshore. As the first big eddies appear that indicate we are entering the faster tide stream created by the point of Brecqhou itself, the castle appears to be moving left at an alarming rate, the same way a platform bench might look as your train departs from the station. It’s blindingly obvious that for this final leg to clear this point, we’re going to have to paddle hard to get across the tide stream and enter the sheltered water on the south side of Brecqhou. If we don’t manage to clear the point, we won’t be going to Sark at all. We’ll just have to head back out to sea, going southwest with the tide towards the distant coast of Brittany beyond the horizon, and wait for the stream to change direction in two hours before heading back to Guernsey. That was the Plan B. At sea, you always need a Plan B. Neither of us were particularly enthusiastic about this one.

Dorka is slightly to the north of my position. We’re both paddling at full race-pace now, with high cadence strokes, tensed cores, and maximum concentration. We only look up occasionally to check our course. Under our boards, the tide rushes and swirls, eddies and counter-eddies. It feels as if we’re approaching the far bank of the greatest river on Earth, and in a way, we are. It feels like we’re being pulled sideways at six or seven knots – way faster than our forward speed. There’s virtually no wind, yet the sea is alive with the pull and torque of the tide. It’s an awe-inspiring place to be.

Finally, after what seems like a long time but was really just fifteen minutes, we clear the small rock known as ‘Givaude’ that lies a few hundred metres southwest of Brecqhou, and we’re finally in calmer water sheltered from the main tidal flow. La Grande Grève beach now appears dead ahead: we’ve made it to Sark. It’s almost low water, and the exposed sand glistens darkly in the afternoon sun. A few yachts are anchored in the bay. It’s a tranquil scene, so far removed from what we experienced in order to get here. I hear the nose of my board slew into the sand: touchdown. Dorka lands just after me. There are fist bumps and laughter. We did it – or at least half of it.

We carry the boards up the beach, away from the incoming tide. We need calories and fluid, in that order. Salami, nuts and energy bars are inhaled with half a litre of water and the last of the coffee. We hike up the beach, and scramble up the ultra-steep, falling-down concrete steps that lead up to La Coupée. It’s Sark’s most famous feature, and arguably Britain’s strangest and most spectacular road. It is essentially a track along a knife edge ridge that separates Sark from Little Sark, the peninsula on the southern point of the island. There are cliffs on both sides going straight down to the sea. It’s too narrow for a car, and there aren’t any of them on Sark in any case. It is perfectly designed, however, for a small sit-on-top tractor, the defacto mode of motorised transport on this beguiling little island. On cue, just such a tractor chugs down the hill and across the ridge – or is it a bridge – as we arrive. The scene from up here is serene. The large island of Jersey sleeps on the horizon to the south, tidal eddies dance around the visible coasts to the east and west, and the route we’ve just taken to get here stretches out beyond, first to Herm, and then the distant coast of Guernsey glimmering in the late afternoon sunlight.

The sweet view of success from La Coupée

The voyage back

We push out and paddle west into the sun. The wind has died, and the sea shines darkly in the liquid light. It’s utterly idyllic. Soon we’re out beyond the point of Brecqhou; it’s nothing like it was an hour and a half before, when we came this way through that river of swirling water cranking southwest. The stream has slackened off; it’s now just before the turn of the tide. We make a reckoning point just to port of the tiny island of Jethou, which lies immediately south of Herm, to give us a course back across the Grand Russel. The tide will first pull us slightly south, then back north as the stream changes direction.

We glide back across the Grand Russel as the midsummer afternoon slips slowly, imperceptibly, into evening. And what an evening it is. One of wildest sea channels in the British Isles is, for now, a filmic scene of total calm. A powerboat heading east for Sark passes well north of us at thirty knots before coming slowly off throttle and circling around. We think perhaps they’ve seen puffins, but actually they’ve just seen us. They slowly approach. We give them the thumbs up. They wave us on. The middle of the Grand Russel is not, I suppose, the most likely place to see loaded race boards.

As we approach Jethou, the north-flowing stream gets going. A large rock topped with a brilliant white obelisk called La Grande Fauconniere lies just southeast of Jethou, and makes a useful reference point as we close in. At first, we think we can clear Jethou to the south, but the way the obelisk starts moving as we near the islands proves otherwise. We’re being pulled north with the early flood stream, so we’re going to have to use the Percée Passage, the narrow and spectacular channel between Jethou and Herm, to get back into the Little Russel and return to Guernsey.

We eddy-hop the tide and come close inshore to the outer rocks, and soon we’re entering calmer water on the north side of Jethou. The island is privately owned so we don’t land, but have a quick break for some snacks and fluid in the shallow channel between Jethou and Crevichon, another islet directly north. Now we’re back in the Little Russel proper; it’s just a short ferry glide of a few kilometres across to Bordeaux Quay on Guernsey and our launch point. This time, we keep the Brehon Tower well to port. We’re on a true diagonal vector now, letting the tide do at least some of the work of taking us back to base.

The afternoon has slipped into a perfect midsummer evening. A few boats are either returning back to St. Peter Port or heading out for the night. We get the final tidal vector almost exactly right – third time lucky – and we approach the big offshore rock beyond Bordeaux Quay just upstream of the main flow. The tidal stream is going at full chat now, and we come into the final turn of the voyage flying alongside the rock’s seaward edge at a solid eight knots, woooohoooo. An eddy line catches my fin as I turn around the rock, and I have to brace hard not to fall, but suddenly I’m paddling out of the tide for the final time and towards the beach. Dorka is right behind me. She smiles a big smile as we come into the bay together. A cocker spaniel runs down the beach towards us, barking excitedly as he stares out to sea. He wants a ball from his owner, of course. But secretly I imagine that he somehow knows where we have been today, too.

Home safe

We did exactly what we set out to do, and give or take a few interesting moments – particularly the tidal vectoring on the approach to Sark – it all went to plan. Doing a trip like this is the result of thousands of kilometres of standup paddling in tidal and offshore waters, and combining that level experience with a near-perfect window of sea and weather conditions. Part of the joy of adventures at sea is in seizing the moment, and being in the right place, at the right time, with the right partner or team. For our voyage out to Sark and back, we certainly captured that magic moment of correct ingredients.

The next morning I woke early to the sound of the wind in the treetops. Heavy weather. I made a strong coffee and drove down to the harbour. The sea was grey, and the Little Russel was a surging mass of wind against tide. Big overfalls heaved around the rocks; spray was whipping from the whitecaps. There wasn’t a boat in sight, not even a trawler. I could just make out the bulk of Herm through the mist. Beyond it – nothing. Breakers roared against the shingle, and Sark had vanished to windward.

I listened to the patter of the drizzle on the windscreen, squinting out to sea, looking for something I knew was there. That star-shaped dot on the chart we’d travelled to yesterday had shifted from the visible to the imaginary. And perhaps the islands we cannot see but can still vividly imagine are the most spellbinding landmarks of all.