Dave Pickford and Dorka Fekete share their story of the 40km crossing of the Minch by stand up paddleboard. The Minch is the strait in north-west Scotland that separates the inner and outer Hebrides - an exposed stretch of water with some big challenges for paddlers yet providing some beautiful scenery!

The horizon to the west shimmers in the midday heat. It’s nothing more than a dark green mirage above a deep blue surface. In the middle of Minch, we’re making a course for fifteen degrees south of the pointy summit of An Cliseam, the highest peak on the Isle of Harris, that hovers in the distant haze almost eight hundred metres above the waves. It’s a useful waymark for the huge tidal vector we are making across one of the longest and wildest sea lanes of the British Isles. Behind us, on another island we have now left very far behind, the Quiraing forms an unmistakable jagged line along Skye’s northern perimeter. Standing a few centimetres above the sea on our loaded race boards without another vessel in sight, we are fully committed to the voyage, and completely exposed to everything the ocean might throw at us. We’re halfway across the Minch, but we’re only halfway there.

In this article

Touring & Exploring

Adventure & Lifestyle

Travel & Inspiration

The Northwest Highlands of Scotland are one of the very best places in the world to explore by sea. A yacht, sea kayak, or even a standup paddleboard are the ideal form of exploratory transport in this most spectacular of regions. In 2021, I made a relatively short trip from Elgol on the southern part of the Isle of Skye across Loch Scavaig, up to the Coruisk basin and back around the island of Soay, right below the awesome Black Cuillin, which was more than enough to get fired up for a more substantial open water voyage in the area.

In good conditions, experienced sea kayakers often paddle across the Minch, the great sea lane that separates the Inner and Outer Hebrides. Its name in Gaelic, Sruthnam Fear Gorm, means ‘Stream of the Blue Men’. In Scottish folklore, these mythical beings were reported to swim out from the Shiant islands to capsize passing ships, but could be thwarted by skilled pilots.

My partner, Dorka Fekete, suggested after our trip out to Lundy in 2022 by SUP that we should see if it was possible to do this crossing, too, by standup paddleboard. She’s one of the few people I know capable of doing a trip like this by SUP, and also one of the only people I know who’s crazy enough to suggest it. It’s about the same distance as the Lundy trip but considerably more difficult. This is because the tide doesn’t flow with you, as with the Lundy crossing, but rather across the course you must take. The complexity and commitment of a paddle like this is of a different order of magnitude than one for which the tidal current flows in your favour.

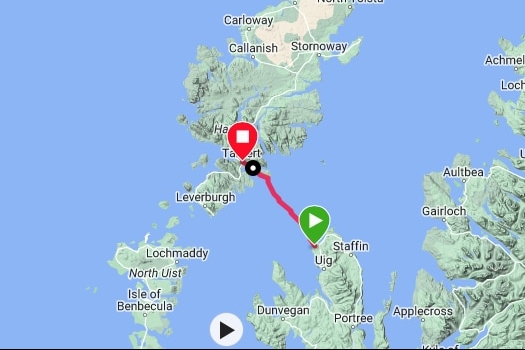

To cross the Minch in a kayak or with a SUP, you need to use tidal vectors all the way, adjusting your course to take into account the constant lateral drift from the tide. There are various ways of doing it, but we settled on the classic crossing from Camas Mor on the north coast of Skye to Tarbert on the Isle of Harris. This has the major advantage of being able to return directly on the CalMac ferry to Skye. Some kayakers do this over two days, stopping en route on the Shiant islands. Dorka and I, however, felt the big attraction of the crossing was to do it – or at least try to do it – in a single day. A fallout plan if the tidal vectoring didn’t work, of course, would be to have an enforced bivouac on the Shiants and do the final leg to Harris the following day.

Towards the end of a prolonged period of high pressure in the early summer of 2023, the sea conditions were as good as they get. We camped at Camas Mor after the long drive north from the south of England, and woke to an azure morning that was much more akin to the Aegean than the north of Scotland. The next couple of hours were preoccupied with sorting lots of offshore gear and getting the boards ready, along with the crucial preparation of a hearty breakfast. By eleven o’clock, we were finally set, and pushed out into the Minch at low water from the shingle beach.

The islands of Fladda-chùain glimmered to the northwest, and in the distance we could just make out the dramatic profiles of Harris and Lewis against the western sky. In the anticyclonic haze, they looked very far away. It can be intimidating setting off on an offshore crossing like this for a destination you can barely see, but that also defines the beauty and commitment of offshore paddling.

We passed the prominent rocks that lie about four kilometres offshore well to our south; we would follow a north-westerly tidal vector for the first section of the crossing, because our destination is due north-northwest but the flooding tide will be dragging us northeast for the next few hours. The stench of guano is overwhelming downwind of the rocks, which are home to a vast collection of seabirds.

We see razorbills, kittiwakes, cormorants, and the first of a huge number of puffins floating on the water beside us. Not long after, a submerged bow-wave creates a strange swelling in the sea about a kilometre to the west, and the distinctive fin of a Vanguard-class nuclear submarine appears. From their base in Faslane on the Firth of Clyde, the Royal Navy use the Minch extensively for submarine training exercises, and the arrival of a Chinook helicopter above the vessel at the same time confirms that’s exactly what’s going on here today.

Time passes and we continue on north-westwards.The submarine and helicopter disappear, and a pair of dolphins breach the water to the north. We are surrounded by an unbelievable number of puffins, far more than I have ever previously seen at sea. By 2 p.m. we’re pretty much right in the middle of the Minch, more than ten nautical miles off the Isle of Skye and a similar distance from the east coast of Harris.

On a day like this, we’re really in quite the location to be standing on a couple of fourteen foot paddleboards.

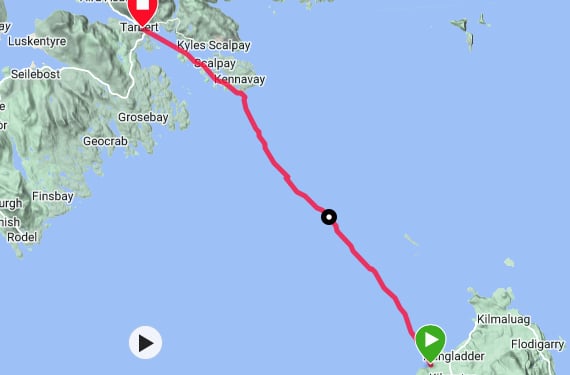

Our cruising speed starts to decrease slightly as we approach the Isle of Scalpay, a small island which lies directly off the east coast of Harris. We’re still following the northwesterly tidal vector we’ve been using all the way across, which has put us in exactly the right position on our approach to the Outer Hebrides. When we take a short break, Dorka notices on her Garmin GPS that our drift angle has changed: the shape of Scalpay, as I had suspected it might, is deflecting the tide hereabouts. The stream, therefore, is against us, and the final few kilometres on the approach to Scalpay are by far the hardest part of the trip, with the Shiant islands looming large in the distance. But would the Blue Men of the Minch swim out to scuttle us?

I ask Dorka what precise direction she thinks the stream is flowing in. Directly due northeast, she says. The tide is now taking us away from the Outer Hebrides and more or less directly towards, er, the Shetland Islands, which are some 400 kilometres away across the North Atlantic Ocean. Dorka has a PhD in theoretical probability, so I tell her she should set the final tidal vector for our approach, as getting it wrong is not an option. “Let’s go 290 degrees west-northwest, that should do it” she replies. And that way we go, paddling into the falling sun.

The bright red-and-white striped Eilean Glas lighthouse on Scalpay’s eastern point stays to our north, although the tide is still trying to drag us eastwards and out to sea on the final approach. We decide to make landfall in a small cove on the south side of Scalpay to have a proper rest. As we pull the boards up on the barnacle encrusted rocks, I realise we’ve just crossed the Stream of the Blue Men and made it to the Outer Hebrides. It’s a great feeling. A pair of Arctic terns swoop in to greet us, their distinctive hooked wings sketching shapes in the evening air.

After a much-needed break, we’re back on the water and weaving through the sheltered channels and maze of tiny islets and islands off the southwest coast of Scalpay. Finally, our destination appears in the gold light of evening, and we land on the floating pontoon of the Tarbert marina just before eight o’clock after almost exactly 40 kilometres of paddling. The crossing has taken us just over nine hours.

Heading up the hill to the Harris Hotel for a well-earned pint, I reflect on what’s perhaps been the best offshore trip I’ve yet done on a paddleboard. In the midsummer evening light we can just make out the shape of Skye in the distance, like a long mirage across that tide-enchanted sea.

Extreme Horizons

In Extreme Horizons, we set forth on an extraordinary journey of discovery through climbing, adventure motorcycling, wilderness travel, and nautical expeditions in some of the wildest places in Britain and across the world. From first ascents of cutting-edge climbs to a series of pioneering and unusual sea voyages, and from the dust of the road less travelled to the secret summits of remote mountain ranges, this is the remarkable story of a lifetime’s quest for uncharted terrain.

What do we learn from encounters with wild and hostile environments? The experience of physical risk, the relationship between uncertainty and choice, the deep psychology of exploration, and the moral value of adventure and fellowship are central themes of this fascinating and far-reaching book. Extreme Horizons is a veritable treasure trove of stories, insights and perspectives for die-hard adventurers and casual enthusiasts alike, and essential reading for the committed armchair explorer at the same time. As a fully illustrated edition, this book is a collector’s item for any outdoor enthusiast’s bookshelf.