A SUP paddle is just a paddle right? Wrong! SUP paddles come in all shapes and sizes, and choosing the right one is just as important as choosing the right board, especially on race day. But how can you find out what race paddle is fastest for you? Regular SUPboarder contributor and testing guru Dr Bryce Dyer puts 3 paddles to the test and explains what other factors are important to consider when choosing the right race paddle for you…

Board Testing 101 – How to find out what race paddle is fastest for you

In a recent article on SUPboardermag, I provided some guidelines of how to test flatwater race boards and hopefully demonstrated that beyond the colour, hype or marketing, that board choice is an individual thing, the answer could have a real impact on your performance and that you can test this yourself. However, this is only one element of what dictates your speed. Another obvious factor is paddle choice. Paddles vary in shape, size, length and material so you might be asking if there is a real difference between these and could the right choice make you a faster paddler? The driver for this question for me was the recent Naish N1SCO one design national championships that had three different races of three different distances. I was wondering if one paddle could be more advantageous over another. The only way to find out was for me to develop more test protocols, run some experiments and then trawl through the data.

To run some paddle tests, I used a secluded reservoir with calm water, surrounded by trees and tested early in the morning to provide controlled conditions that were free from wind and currents. This test environment may not be representative of your races but it provides ‘clean’ conditions to then perform a statistical analysis to see how robust your testing protocol is. If these results are good, you can then expand or rerun the tests with more chaotic weather or water states to increase the level of specificity you might experience in your own types of races. However, there will come a point when the level of chaos in a test environment becomes too great and will lead to the data having too great a margin of error (e.g. data ‘noise’). Its best to start simple and work up from there. Here’s how I did it and anyone with some time and effort can achieve the same.

Methods

I’m a scientist by trade so its good professional policy to reveal up front any conflicts of interests that I may have before you judge my results. In this case I’m a brand ambassador for Quickblade (courtesy of The SUP Hut). Therefore this study was intentionally limited to using their paddles but I decided not to test ‘head to head’ against other brands so that any obvious brand bias on my part would be minimised. For this case study, I compared two popular racing paddles. These were the Quickblade Trifecta 86 and the V Drive 91. However, to act as an extreme comparison, I also tested the ‘Big Mama Kalama’. This is a shoulder shredding (and frankly a colossal spade shoveller) of 120sq centimetres of paddle blade fun – I really love it but it’s not for the faint hearted. All 3 paddles were the same total length (85 inches in my case). There is an argument though that the blades themselves vary in length so you could standardise paddles you test based on either shaft length or total length. Both methods would likely influence the results so this is a decision you’ll need to be aware of up front.

To perform the test you’ll need to record the following metrics when paddling your chosen race board. These are: time, distance, speed, average speed and stroke rate (Note: stroke rate is not always available on many GPS devices but you could technically count a fixed number of strokes in your head and then stop paddling to see in your data file where each run took place). I am supported by Nielsen Kellerman this year so I used their Speedcoach 2 GPS device to show my stroke rate in real time. You’ll need to use the same stretch (and direction) of water that is approximately 2-3 minutes long or around 300 metres in length. This kind of length has been used successfully in scientific literature before to detect the differences in paddle sport equipment changes. I finally record the weather from the nearest local weather station using a website like Wunderground after the tests to see how the weather might have changed while I tested or if I get different results in the future. I used the same board for all of the runs and my feet position was marked with tape to ensure board trim was standardised across the full battery of tests.

The key thing with any testing that I do is to perform as many test runs that time allows, calculate their margin of errors (I use standard deviation in Microsoft Excel for this) and to alternate (or randomise) the equipment you are testing to minimise the impact of changing weather. I performed two different tests with the three paddles and this took around 2 hours for me to complete. Remember that the results are unique to the paddler and the test environment they were performed at. The two tests I performed were as follows:

1) 300m Race Pace Testing at 9kph. 9kph is my typical long distance race pace on water like this. It’s important that you test equipment at the pace that you would typically compete at as this will see the board running as you’d see it in your races. I paddled over the same 300m straight line – changing sides with the paddle to hold the course. At the end of each run, I would paddle at a very light pace back to the start and then begin again. I completed 6-8 runs of each paddle (randomly alternating the paddles) and had to reject a couple of the final runs as the wind was rising in strength and started to affect the results.

There are two key metrics that were then calculated afterwards that formed the major part of determining the differences for me between the three paddles. The first was my ‘I/O ratio’. This is my average stroke rate per minute for a test run divided by its average speed in kilometres per hour. This normalises the small differences in either speed or stroke rate that you would likely see run to run and gives the ability to better directly compare them. The lower the ratio value, the more effective the paddling was. The second key metric I used was my recommended to me by Canadian C1 coach and Team Starboard athlete Larry Cain. This metric was based on the premise that it had been found that neither stroke length alone nor stroke-based accelerations correlated as a key performance indicator for canoe or kayak paddling. The problem with distance per stroke is that it will vary based on paddling speed and that the stroke length is typically longer at slower paddling speeds and shortens with increasingly faster ones. To address this, Cain proposes use of a ‘Stroke Effectiveness’ metric. I then searched some scientific journal databases and discovered that this concept has been used reliably in many scientific studies for over two decades in other water sports that involve human propulsion (such as swimming or rowing) and is known generally there as the ‘Stroke Index’ (SI). To calculate your SI, you merely multiply your average speed in metres per second for a test run by its average distance per stroke in metres. If you’re wondering how to find out your average distance per stroke easily, just divide the length of your test run by the number of strokes you took to perform it. You’ll likely find your distance per stroke is typically somewhere in the 3-4 metre range and the larger the SI score, the more effective and efficient your paddling is. This is how you’ll see what paddle is best for you.

2) 15 Stroke Sprint Paddling. This second test won’t likely be that useful for you but was designed for my specific needs of the very short sprint or punchy style of N1SCO races that I’m doing this year. I wanted to check how the board accelerates under controlled conditions using each paddle for a fixed number of strokes on one side. 15 strokes on my right hand side were then applied as hard and as quickly as possible to get the board to its highest possible speed. A short recovery between each sprint took place and I completed 6-8 runs using a randomised choice of paddle. Bear in mind that paddle choice won’t just be affected by what it does below the water but also above it. For example, the paddles overall weight, position of its centre of mass and blade size will influence your results due to the moment of inertia of the paddle (how hard it is to swing it through the air) and any aerodynamic drag created by the blade (being feathered and moved through the air to set up for the next stroke). In this test I was going to be looking at the maximum speed of the board obtained and then calculated my boards acceleration for each run (the increase in speed divided by the time it took to achieve it).

Results

First, let’s look at the 9kph speed trials.

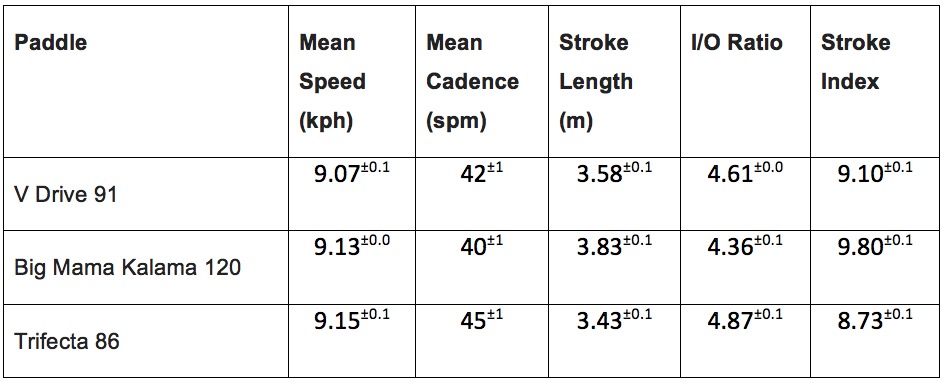

You’ll see in the table that each paddle performed distinctly differently from each other and my testing produced very low margins of error. In fact my data variability of each metric was typically only 1% which is as good as I typically see in sports science studies performed in a laboratory. Put simply, if you’re careful in your study design, you can get some great quality test data. As you’d expect from different blade sizes though, the stroke rate required to hold 9kph differed slightly between the three paddles.

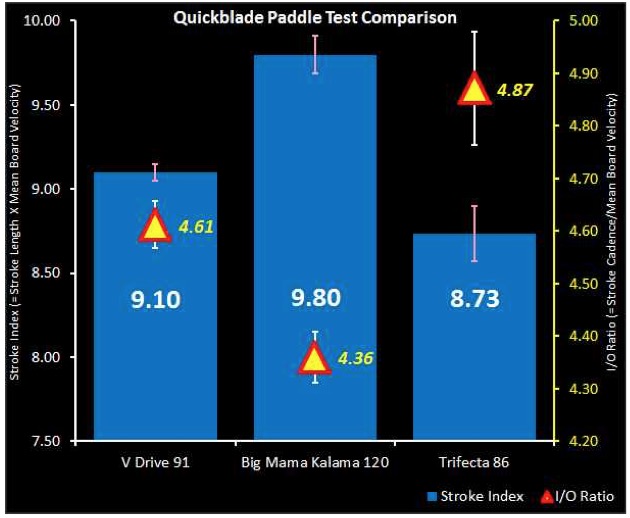

I’ve taken this information and illustrated it in a graph for you below.

In this, the blue bars show the clear difference in the stroke index between each paddle and the white error bars are at the top of each blue bar showing the margins of error. As you’ll see, the Big Mama Kalama proved highly efficient and the Trifecta 86 proved the least efficient for me. The keen of eye might also notice that the margin of error is a little higher on the Trifecta 86 than the other two. This was due to the increasing wind strength that took place towards the end of my testing (that I mentioned earlier) so I abandoned testing after I’d got 6 runs from it as the results were getting increasingly unstable. Next, the yellow/red triangles on this graph show the I/O score for each paddle. Ideally then, you want to see the highest SI value you can get coupled with the lowest I/O score. Surprisingly, the Big Mama Kalama came out top here and was nearly 10% more effective than the V drive 91. The Trifecta 86 did not perform as well for me as the other two.

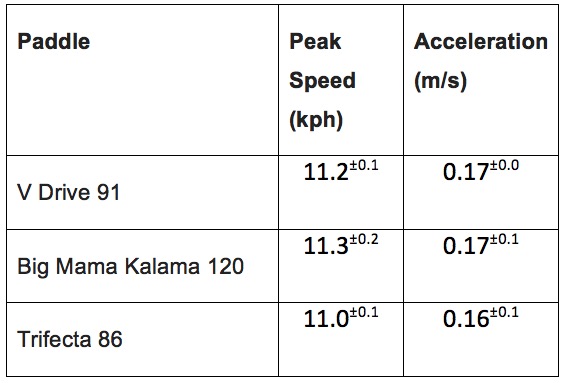

Now let’s look at the 15 stroke acceleration tests:

The Big Mama Kalama achieved the highest max speed but the results of both this and the V Drive 91 are within each other’s margin of error so could be assumed to be virtually the same. The Trifecta accelerated fractionally slower than the other two. You could argue that due to its smaller blade, it would need more than 15 strokes to get upto the same speed as the others but my data showed that it would have needed even more time to do it. This might seem odd but I suspect that it’s most likely that my technique using this design frankly degraded when trying to paddle so fast and so hard. Alternatively, the V Drive 91 has a very secure catch for its small size and reached its peak speed far faster than the other two so this would seem to be the best choice for me here.

Discussion

Whilst you might think it odd that a huge blade like the Big Mama Kalama would do so well in both tests, there might be evidence in the literature why this is. In cycling for example, low crank cadences have been shown to demonstrate far higher physical economy and efficiencies than those performed at higher cadences. Does this mean then that I should be using the biggest blade I can ? – the answer to this has two important considerations first. The first is that my test runs were short in duration and that any physical fatigue was therefore low. However, take a paddle that large into a race over 10 miles and you might soon see a different story. If the blade is big and the cadence low, the muscular strain is going to be larger than a smaller blade and the research I mentioned before about cycling cadences supports this. The efficiency over short distances might not actually convert up into being sustainable over longer ones. However, the second key point is finding out whether it is possible through careful training and adaptation whether you could train yourself to use it over much longer periods of time. Using low key races and longer paddles should reveal the truth there.

Alternatively then, does this mean that the Trifecta 86 is a bad paddle choice for me? The answer is… possibly for sprinting… but then maybe not wholesale. I use that paddle for any race I do that is longer than about 90 minutes in length as its small size minimises my muscular fatigue and keeps me fresher during the final key stages of a race. There certainly has been a trend of late by pro paddlers to downsize their blade size. However, it does require a higher cadence to use it which will place a higher demand on your aerobic fitness (notably your VO2 max). In my own case, my technical skills in board paddling are – I would openly concede, quite poor but I do log a relatively high volume of weekly training compared to most and I have 20 years of consistent endurance training behind me. My raw fitness is likely to be relatively high. Put simply, this paddle is not as efficient for me but I train accordingly to deal with it. Where I would clearly benefit though is to direct some training time to improve the quality of my stroke phases when using it to increase my stroke index score. In your own case, you might not be a pro paddler or you might not be as fit as you’d like so following the trend and going for a small blade size might not actually be the best option for you. As a result – test, test, test!

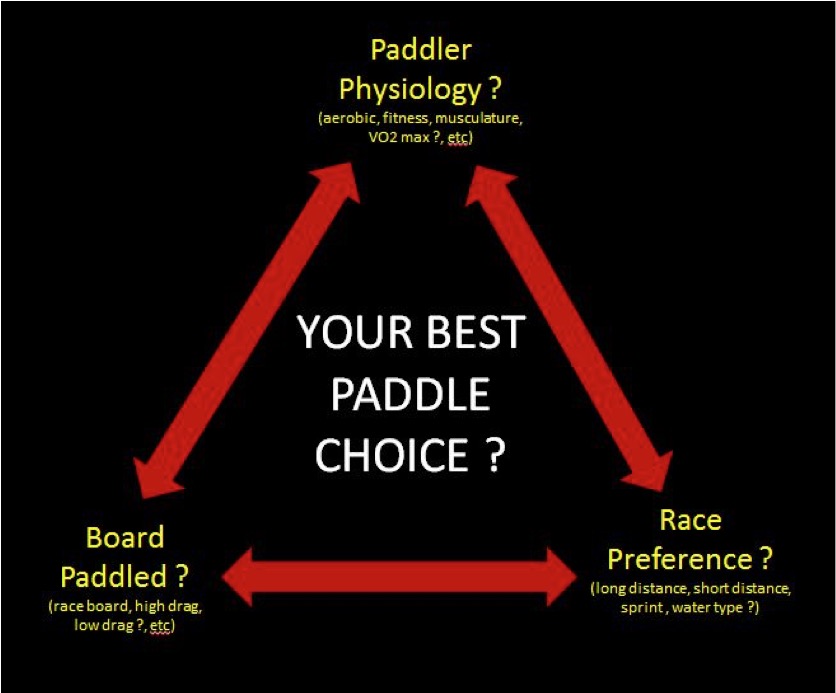

To really summarise what my thoughts on this are, here’s a diagram for how I would summarise the three major factors you should consider when choosing or testing paddles. Put simply, the right paddle for one person may not be the right for another. Choose your next paddle based on awareness of the three points of this triangle and you’ll be better informed than most when you’re making your next purchase.

Ultimately, the take-home message for you is to see that even when using the same board, not only can you field test reliably, but that you can also obtain a huge difference in performance just by changing what paddle you use (and that’s a lot cheaper than a new board!). For me personally though, at my last event (which involved a 100m sprint, a mile long technical race and a long distance race), I ended up using a different paddle for all 3 races. Food for thought…

Words : Dr Bryce Dyer

Some more fascinating findings from Bryce, which clearly show that thinking about what paddle you use is just as important as thinking about your board on race day. So don’t just choose the one your SUPboarder idol is paddling with, or just stick to your old favourite. Get out there and try a variety of paddle shapes and sizes for yourself to see what difference it makes. A different paddle might be all it takes to get you on that podium this summer!

Want to read more? Check out other articles by Dr Bryce Dyer here.

Just came across this article. Thanks for your scientific approach to SUP testing. I have enjoyed other articles and videos of yours! I’m curious why heart rate isn’t included in the data collected to ensure energy expenditure is the same for each run (or if not the same, does it correlate with the difference in SI between paddles, or whatever is being tested)? Also, not sure if you’ve seen this, but your field testing of blade size supports what has been shown mathematically – https://thescienceofpaddling.net/part-5-what-moves-you. The longer stroke length with the larger paddle also fits with what has been taught… Read more »

So many good points here Aaron. What I’ve done is to cherry pick a few of your excellent observations and will attempt to address them. 1) I’m curious why heart rate isn’t included in the data collected to ensure energy expenditure is the same for each run. ANSWER: This was purely due to the relatively short duration of each run. I’d only use HR as a metric myself if I were doing runs of at least 5 minutes long. With short durations of just a couple of minutes (like I used in these kinds of tests), you’re drawing on a… Read more »

Thanks for the lengthy reply Bryce! I appreciate your explanations and thoughts on all this.

I am interested in the UV88 Trifecta perhaps to reduce fatigue or oneset of tendonitis… I usually use Kanaha 90 perhaps a bit shorter than need, this fixed a shoulder issue I had with longer paddles. at 6’4 my regular paddle for sup surf ~81 is slightly short for me for racing. I’ll do a couple 5mi trips a week on the Bullet. Any thoughts on increased cadence and slightly different blade. UV88 composite blade being longer, thinner, scouped and the shaft being approx 4″ longer ~85″. I think blade angle is same, 10 deg… no 12 deg offered…

Hi Ryan, the UV88 has that elongated, narrower blade like you mentioned and this will take the strain off your joints. You’ll need to paddle at a higher cadence with this paddle in order to keep pace, but the benefits of using this for racing or faster long distance paddling is worth it to reduce fatigue. As for the length, before gluing anything, I’d cut the paddle a little longer to begin with and just tape the handle with electrical tape. That way, for the first couple of paddles you can work out if you need to take off more… Read more »