Have you been thinking about taking part in your first SUP event this year or are you hoping to improve your results by doing a bit of training, but no idea where to begin? Fear not! Regular SUPboarder contributor and Naish UK team paddler Dr Bryce Dyer is back, with a two part series providing some excellent guidance to get you ready for that first race of the season. Over to Bryce…

SUP is unique when compared to a lot of other endurance sports. It’s a lot newer for a start but the paddlers themselves have often come into it from a wide range of backgrounds. Some are surfers, triathletes or fitness fanatics. Some however, don’t have any athletic background at all and purely got into it as something they saw, fancied a go and then later felt like trying a race. The problem is that SUP’s relative infancy often sees many training or paddling without a plan and there is a lack of specific information out there for those who would like to improve their results. Understanding what is needed can be confusing to some and more often than not, people are swayed by what their heroes and the race winners are doing (which isn’t always a great idea). As a result, I thought I’d give you a bit of a primer into stripping down the basic concepts and provide a bit of insight into how you can train for any particular SUP event – in this case, one of the Naish One Design (N1SCO) events.

As always from me, here are the disclosures – firstly, always check with your doctor or physician before starting a training programme. Secondly, this plan is aimed at SUP first timers and novices in particular. These are people who can currently handle upto an hour’s worth of physical exercise. Finally, I’m intentionally trying to keep this simple so that the sessions I’m prescribing are straightforward enough so that anyone with little more than a stopwatch (and a good gauge of how they feel) can undertake them. A lot of what I do myself would overcomplicate the needs of novices and whilst I personally like to have the deck of my boards and the handlebars of my bikes looking like the space shuttle, it’s a fair argument to say that many find any application of science distracting or off-putting. This is a stripped down, intentionally low-fi approach. Now we’ve covered all this, read on.

All right then, the cornerstones to any successful training plan for any kind of sporting event relies on four basic principles. These are:

- Specificity

- Overload

- Recovery

- Progression

In layman’s terms, specificity means that your training should be specific to the needs of the sport, its skills, physiology and distance. In other words, you don’t train for a 10 second sprint by doing a 3 hour paddle any more than I would train for a marathon by doing circuit classes. As for overload this means that the training session should provide some form of physical stress. This doesn’t mean you should be on your knees after every session but you should feel like you did something by the time you get back in your car. Recovery though is the key bit. Contrary to what you might think, you don’t get fitter or faster by training. Instead, you actually get better in what happens after it. Put simply, you push your body’s engine or muscles and they come back stronger or become more efficient. If you ditch the recovery, all you’re going to do is to get is tired, broken down or injured. I often see’s athletes enter a downward spiral whereby they don’t improve so they feel the best resolution is to train even harder until eventually (depressed and despondent), they give up or (for the more stubborn), consistently underperform. The reality is often that they either needed to do a little less or just frankly needed a little more rest. The irony of all of this is that the fitter you get, the more you can handle. I personally have a training load now that I would not have been able to handle 4 or 5 years ago but it’s taken me years to build upto it. However, I know that I can personally sometimes be a slave to the numbers but the reality is you need to listen to your body. The final point is that any training plan requires progression. Your body will get used to what you’re throwing at it so if you don’t keep applying some form of change to your plan, you’re going to get used to it and the improvements will stop. How do we do this ? The reality is that to progress your sessions an athlete should:

- Increase the power

- Reduce the recovery

- Increase the duration

Increasing the power is great but in my experience this is a short term strategy. In SUP, Power is the result of the force at the blade and the stroke rate you are paddling at. One affects the other and if you go too wild, your efficiency can degrade (meaning you’re working hard but not getting the power out as well as you could). In addition, mentally you can’t push past your limits week after week, time after time [it’s why I’m not a huge fan of the fashionable ‘get fit in 7 minutes’ or going to a metafit class – their gains rely entirely on being able to work hard, week after week and it’s not mentally or physically sustainable]. It’s a big ask. If paddlers do the same thing, week in, week out, it’s never going to see them progress past a certain point.

Reducing the recovery though is a useful technique if you’re trying to build up to sustaining a larger block of work at a given speed by doing shorter intervals. It’s particularly good if you’re looking to complete a longer distance event for the first time but it’s not great for increasing your training load. Load is the raw amount of training you’re doing (and is a combination of the impact of the time you accumulate training and the intensity you’re doing it at). Increasing your load progressively (but carefully) is what makes you fitter and faster.

Finally, you can look to increasing your exercise duration. This is great for continuing to increase your training load and improving your aerobic fitness. The problem is that many people have to juggle families, work and other responsibilities so it’s not without a realistic ceiling. For example, I know Olympic track cycling pursuiters who will build up to 4 hour training sessions – despite competing in an event that only lasts 3-4 minutes. The truth is that they are trying to get their aerobic engine as good as they can get it (and have the time to do it). However, I also know of plenty of amateurs who can get 95% of the way there but don’t train any longer than an hour. At the end of the day, its diminishing returns past a certain point and it comes down to your motivation to find that last few percent. On that subject, be aware that pros are pro’s for a reason. The main reason that they are better than we are is often that they have good genetics and work extremely hard….. but also that they can take (and recover from) the training load. Too many athletes try to copy them and end up overtrained or injured. You should train in a way that allows you personally to progress, recover and improve (rinse and repeat !). Doing what a Ryan James or a Jo Hamilton-Vale does – merely because they consistently win races in the UK, is physiological suicide for your average paddler. Those guys spent many years getting to where they are and it’s by no means an accident (as famed exercise physiologist Dr Andrew Coggan once told me, ‘there are no miracles in racing’). Irrespective of who it is, if a paddlers training plan isn’t incorporating these fundamental aspects, they’re not training – they’re just paddling and their improvements will stagnate within a month or two. Doing the same programme, week in, week out won’t help you.

So then, knowing all of this, how can we apply these principles to a sporting event ? Well, for the sake of this article, I’ve chosen a N1SCO SUP racing event and created a short 8 week plan to get a novice paddler physically ready for it. In 2017, there will be three N1SCO events in the UK. These use the Naish One as a one-design format of racing. Everyone has the same board design so the result won’t be influenced by the chequebook. What also makes the event unique to anything else is that each event involves the paddler getting their final placing based upon their accumulated score from 3 separate races held during the day – a short sprint over about 80 metres, a technical race lasting about 15 minutes and a long distance race over 2-3 miles. Each event requires slightly different skills and physiology.

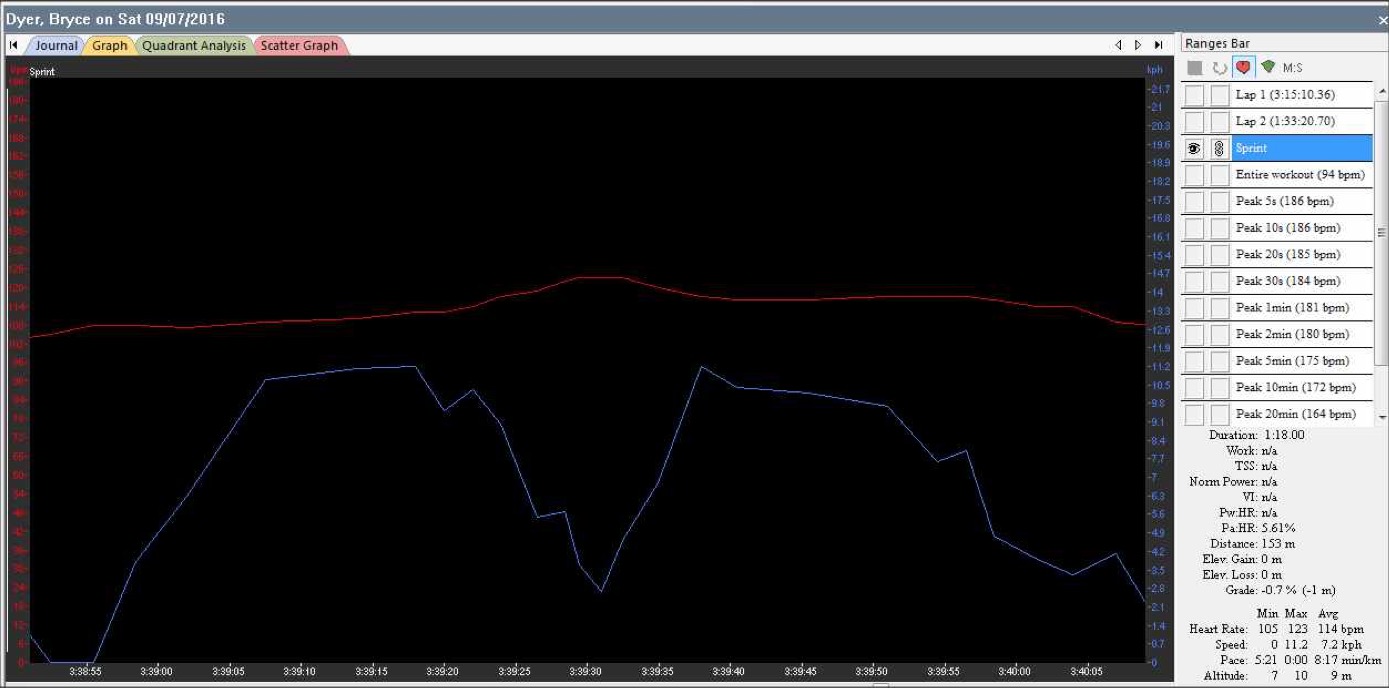

For the final bit of part one, let’s take a quick look at the sprint event first. Once any event gets longer than 35-40 seconds in length, your physiology is being powered entirely by your aerobic system – so that’s where most of your workouts need to be focused on in your training. However, in the sprint, it’s made up of a short effort that relies more on your ability to get upto speed fast through an application of raw power (through the combination of high levels of applied muscle force and stroke rate) and then manage the lactic acid build up as best it can until you complete the event. Take a look of a graph of the speed of a paddler in a typical N1SCO sprint below.

The speed is shown with the blue line. If you look, the paddler gets upto speed as quickly as possible, slows down (as they have to do a single buoy turn) and then accelerates again to get back to the finish line. That’s an event that lasted roughly 50 seconds and had two maximum effort sprints in it (just so as you know, the red line was the heart rate). Heart rate is all but useless in short events as it lags behind any increase in your power output or speed. By the way, this graph also shows how you how you can improve your performance. If you look carefully at the graph, the incline of the line to get upto speed is your acceleration. As a result, improve your power and speed at the start and the time to complete the event will be reduced. Likewise, if you improve your 180 degree buoy turn, you’ll shave huge chunks off your time. You might also have to sprint in a series of qualification heats so you’ll have to recover and then go again. This is a very different prospect to the two other events and requires very different training for it.

In the second part of this article, I’ll go through the other two events and then show you a full training plan to show you how to prepare better for the whole challenge.

Words – Dr Bryce Dyer

So look out for Bryce’s next article in afew weeks time to find out how you can get ready for the 2017 race season. The Naish One Design Series (NISCO) is a great place to start if you’re new to the race scene or after some fun, action packed racing.