In the second of his articles on race analysis Dr Bryce Dyer sums up the BaySUP winter racing series with a series of detailed observations that could help shape your race preparation…

Back in February, you might remember that I did a bit of performance analysis of BaySUP’s winter Frostbite series. By that point, we were at race 4 in the 6 race series with everything still to play for. With the final two races now completed (and the series winners crowned), I did a final bit of analysis on how the frostbite played out and what we can learn from it. Whilst this kind of analysis might seem a little over the top, this isn’t dissimilar to those made famous in the book ‘Moneyball’. The point being, if you’re looking to do well in events, or see what your weakest areas are, undertaking some basic performance analysis like this can prove useful to aid in your decision-making.

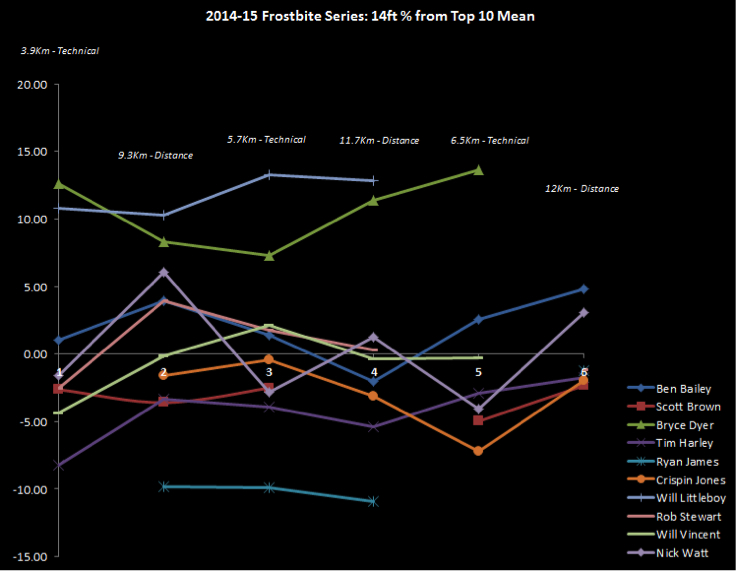

With this in mind, you might recall last time that I presented some graphs of all of the paddler’s performances when compared against a ‘pack average’. This was calculated as the average of the top 10 finishing paddler’s race completion time in each class. Comparing a single paddler to this calculation, may well provide greater insight as to how you are getting on or improving (rather than just comparing yourself to one another which sees greater variation). To illustrate this, let’s use the example of the 14ft class:

The closer to 0% a paddler gets on the vertical axis of the graph, the better they are doing against the calculated pack average. For those that go below 0 into a minus number, that shows they are ahead of the average. There are some interesting things I picked up here. For example, my own performances steadily improved but then worsened in race 4 and 5 (I later found out I had a low-level virus). I cut off the proverbial hand to ‘save the arm’ and opted out of race 6 completely to rest up rather than push my luck. Data like this gave me a heads up that something might be wrong. Alternatively, look at the violet colour zig sagging line of Nick Watt (Starboard UK). This continued the pattern I showed in my last analysis. This highlights a major strength in his surf management and buoy turn skills when compared to others. This kind of insight provides a simple way for a paddler to work out what kind of events might be best for them to race or how to improve their national ranking. By the way, note that whilst Watt’s line zigzags up and down, its general overall trend when looking at races 1-6 actually tracks downwards towards zero. This means that whilst technical events are clearly his strongest suit, he was actually getting better and better generally as the series went on (relative to everyone else).

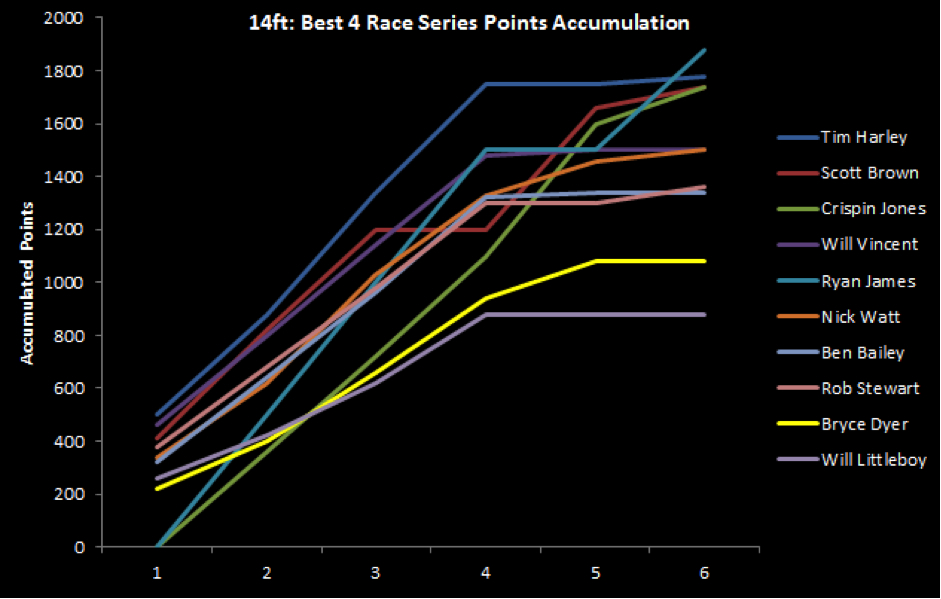

The overall series titles were decided in the last two races and it got very close in the male classes. To help illustrate this, I’ve taken the best 4 accumulated series points of the 10 14ft class guys that all qualified for the series as it went along. As the scores tot up, you can see how a paddler did in the overall. If the line ever goes flat, it just means that their score did not see any improvement after completing the latest race. Here is the 14ft class first:

Race 6 proved critical and saw many changes in the overall. Ryan James’ (Mistral/ZRE) had 3 clear wins notched up before this (but had raced 12’6 instead in race 1 and was away teaching in race 5), so he still needed to finish around 8th or better in race 6 to win the series. That was risky – any kind of mishap and the strongest paddler in the fleet wouldn’t have won anything. Alternatively, the likes of Tim Harley raced every race, had discards to use and his score continued to improve to finally take 2nd overall. Whilst 1st and 2nd might have been clear-cut, the battle for 3rd was looking rather close after race 3. In race 4 the distance race saw high winds. That widened the gaps and eliminated a few paddlers. In race 5’s technical race, there were more bouy turns and more race distance added. That decision eliminated a few more. The final race 6 was the longest distance race yet and that ultimately revealed the final podium. The result wasn’t as clear as you might think though. A hard charging Crispin Jones (Starboard UK) won race 5. This gave him a shot at getting on the overall podium. However, I’d worked out he’d need at least two paddlers between himself and Brown (as well as the win) in race 6 to snatch 3rd from Brown. Jones won a race again but in the end, this only was enough to tie their overall scores. Brown got the final step of the series podium on results count back. You’ll see on the graph here that Jones leapt from 7th to tied 3rd overall between races 4-6. He might well rue the fact he did not have any discards to play with. If there had ever been a 7th race, he may well have been potentially challenging for 2nd overall too.

The series ‘bromance’ of Rob Stewart (West System/Boylos) and Ben Bailey, finally ended in friendly divorce in race 6 when Rob put more than a few guys to the sword by switching from his usual inflatable to a carbon race board. If anyone has any doubt on the importance of board design, Rob moved instantly from placing mid-pack to the front in one race. This excellent result in race 6 then allowed him to overhaul Bailey in the overall series.

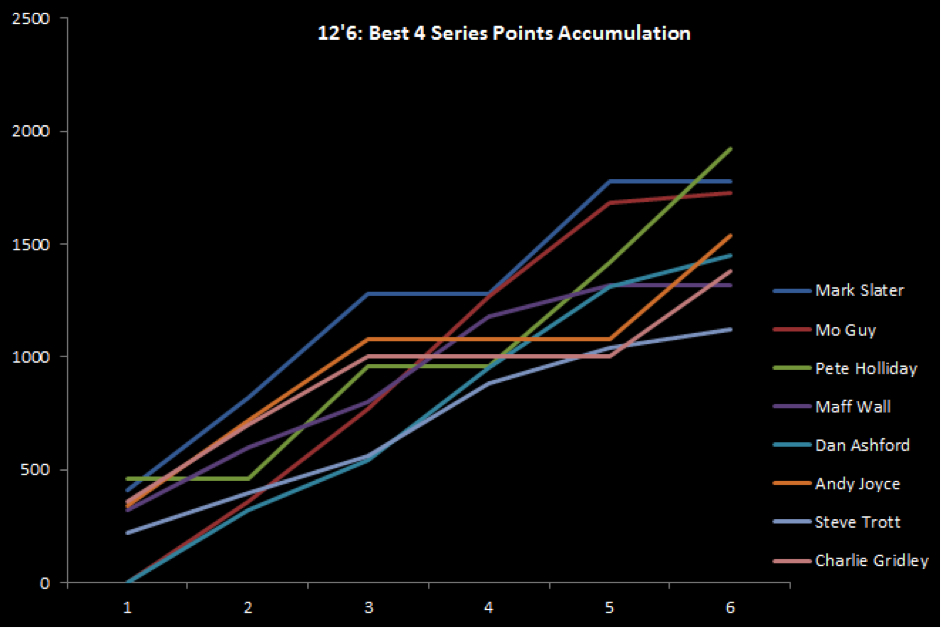

Now, here is the same calculated graph for the guys in the 12’6 class.

Like the 14’s, the same bundle for places in races 5 and 6 was taking place. Pete Holliday (BIC) finally opted for the 12’6 class after race 4. It wasn’t going to be simple result though – you can see in the graph that Mark Slater (Fanatic/ION) was already clearly leading the series by race 5 (blue line). Holliday won race 5 and I worked out that for Slater to win the overall, he would have to win the final race and then have Pete finish in 3rd or worse. In the end Pete did get pushed hard but that was instead from the returning form of Andy Joyce (Starboard UK). Joyce’s surging form in race 6 bodes well for his upcoming world championships. Lastly, the best improver in this class had to be considered as Mo Guy (Jimmy Lewis/Superwiki paddles). He grafted his way up through the fleet from only lying mid pack at race 3 but clawed onto the series podium by race 6.

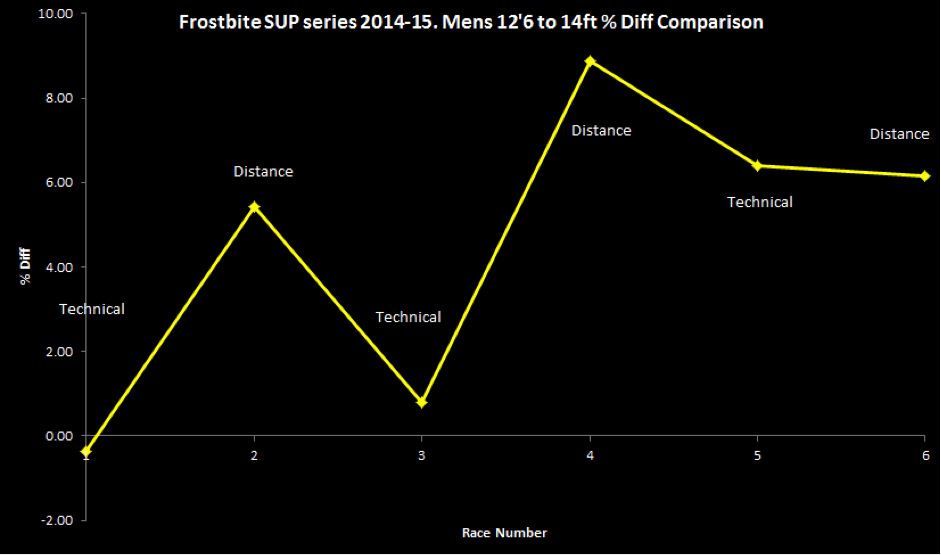

Finally, I posed a question in my last article what difference there was in speed between a 14ft and a 12’6 board? If I were doing this scientifically, the most robust way would be conduct a study between variety of paddlers and boards in a flume tank or a body of water under highly controlled conditions (or to simulate such a comparison within a computer aided design environment). However, to give you a little insight in the meantime, I calculated the percentage difference in the pack average race times in all 6 events between the 12’6 when compared to the 14ft class. What you see is this:

On the whole, as the series went on, the difference between the two board classes widened. The 14ft was typically circa 6% faster than a 12’6 in 4 of the 6 races. However, this calculation would be influenced by who was racing each event. Secondly, notice that when a technical race was held (races 1, 3 but to a lesser extent in 5), see how the gap between board lengths comes down. Why? I suspect that the paddler’s ability to do effective buoy turns and handle the surf has a massive impact on the result in a technical race (rather than just the extra glide speed provided by the longer board). What can you take from this? Well, if you’re going to race a technical event, raw buoy turn speed is critical and well worth practising.

A big thanks to BaySUP for putting on an excellent race series that was safe, varied and fun. It proved a gentle introduction to SUP racing for some and good training involving many of the UK’s top ranked paddlers for others. Hopefully, this will continue into some of the UK’s top events over the next few months.

Words by : Dr Bryce Dyer

So there you have it… a 14′ board might be 6% faster than a 12′ 6″ board in the right conditions with the right paddler, but it’s not all about the board. Fitness and good technique make the difference between podium places. Good luck with your next race!

If you missed Bryce’s first article, you can check it out here.